After the U.S. economy grew in 2021 at its fastest pace since 1984 despite the continuing pandemic, economists are less optimistic about this year as a result of rising inflation and interest rates as well as the implications from the war in Ukraine. William Blair’s London-based macroeconomist Richard de Chazal, CFA, who has more than two decades of experience analyzing the U.S. economy and financial markets, shares his midyear economic outlook.

The most recent U.S. economic data shows that while growth is clearly starting to moderate in some areas, it is not collapsing.

Demand for labor remains strong and household balance sheets are in the best shape they have been in decades. Consumers increased savings and lowered debt during the pandemic. In addition, extremely low interest rates have been locked in for years, if not decades, by both households and the corporate sector, helping provide a buffer against near-term rate increases.

Following last year’s robust 5.7% U.S. GDP growth, first-quarter real GDP declined at a 1.6% annual rate reflecting decreases in private inventory investment, exports, and government spending. In contrast, spending by the domestic private sector as gauged by real final sales to private domestic purchasers, which excludes the impact from trade, inventories, and the government sector, rose by 3.0%. That increase came as the labor market remained strong and wages have increased.

Meanwhile, with the reopening of world economies, the desire to revisit friends and relatives, and the urge to undertake life-affirming experiences as COVID fears ease, consumers are increasingly rotating their spending back toward the consumption of services and away from durable goods, and companies are gearing up for a summer surge in travel and entertainment.

On the corporate side, the manufacturing industry is seeing strong demand across most areas, although it continues to struggle with supply chain disruptions. The inventory-to-sales ratio of the automobile sector, for example, is the lowest it’s been in recorded history, which is indicative of significant pent-up demand.

These factors have led most economists to expect U.S. GDP to rebound at an annualized rate near 2.5% in the second quarter, but lower than their initial forecasts three to four months ago amid the Russian invasion of Ukraine, inflationary pressures, and the Fed’s tightening monetary policy. Currently, the Federal Reserve is forecasting GPD growth in the 1.5% to 1.9% range for 2022.

Uncertainty

There is no doubt that we also are plagued by a tremendous amount of uncertainty at the moment. Investors and business leaders are keeping a close eye on inflation and interest rates as higher levels weigh on economic activity and keep pressure on financial markets.

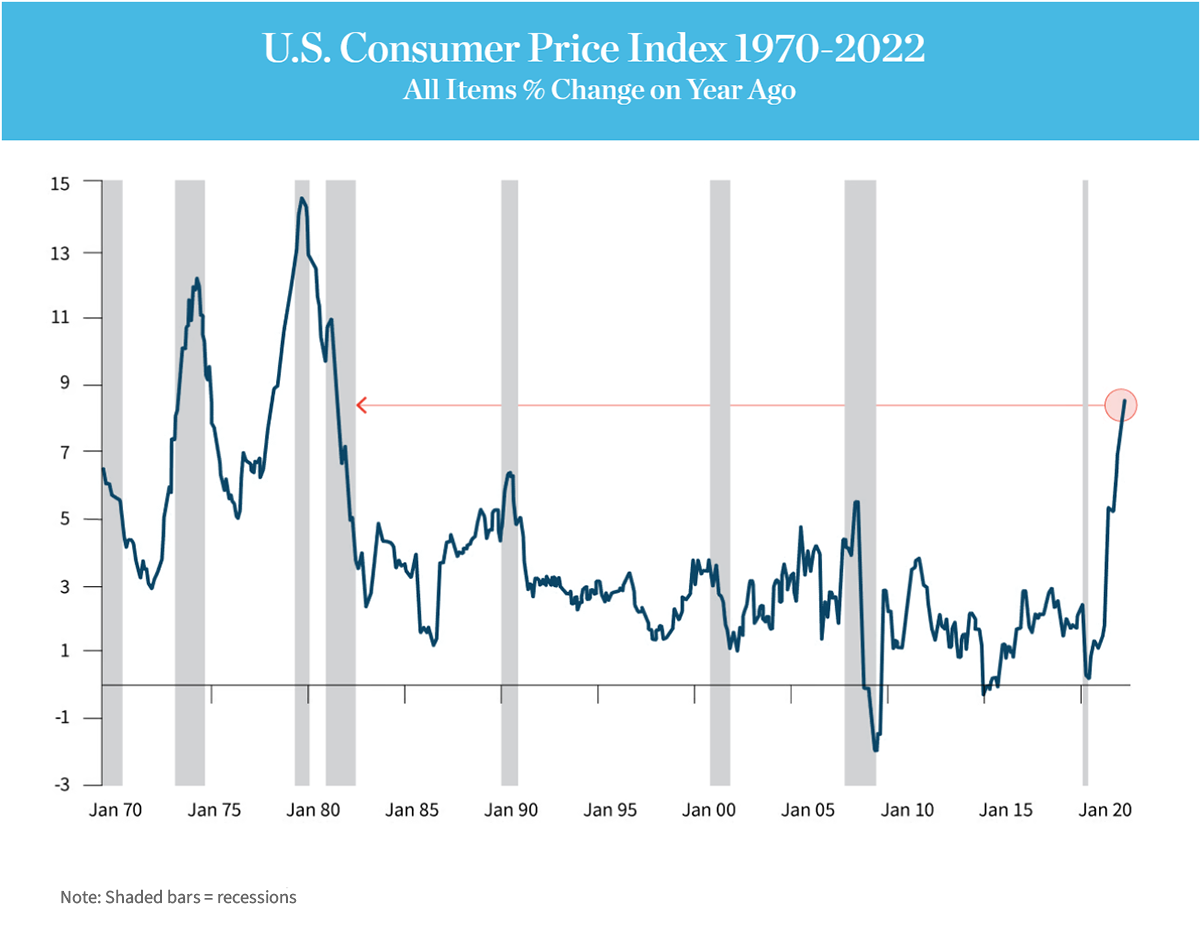

Inflation has returned to rates not seen since 1981. Many factors have contributed to the rise: two years of supply-chain disruptions brought on by COVID; frayed geopolitical tensions; the Russia-Ukraine war and sanctions on some of the largest global commodity producers; China’s new policy of common prosperity; companies re-shoring/near-shoring production; the transition to cleaner energy.

Note: Shaded bars = recessions; Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, William Blair Equity Research

For consumers, large price increases for food, energy, and shelter have already resulted in a sharp decline in consumer sentiment. This is also starting to emerge in some areas of economic activity, such as retail sales and housing. Much pain is already being felt by lower-income households. Corporate earnings guidance has unsurprisingly also started to become more conservative in these areas, and the prospects of a recession in the coming year have increased.

Inflation Spike

The inflation spike is also leading some economists and market analysts to conclude that higher inflation will be the new-normal.

Yet we should not be too quick to jump on this bandwagon. While it seems as though the risks for inflation will be more evenly balanced going forward—after grinding lower for decades—this by no means implies that we are now at the start of a period of radically higher and sustained inflation for decades to come.

The reality is that many of the powerful trends that helped lower inflation in the past are far from over; in some cases, other newer ones are just emerging. As the recent COVID episode clearly highlighted, innovation is far from dead. This is particularly true in areas such as healthcare and technology, which are being aided by digitization—a still rapidly accelerating trend. And while we may be seeing a slowing and/or retracement in the rate of globalization for goods, we are still really only at the very start of the next wave of globalization—the globalization of services.

Fed Watch

Despite the Fed’s initial inflation misstep, it would also be foolish to underestimate the current resolve of the Fed and other central banks, who have been telling us that they will now do whatever it takes to restore price stability.

Over the past few months, the Federal Reserve and central banks around the world have begun tightening financial conditions by raising interest rates and taking on other measures to curb inflation.

So far, the Fed has increased its benchmark overnight interest rate by 150 basis points this year—its first increases in 2-1/2 years—and it has signaled that there are more to come. The Fed now feels that given the strength in the economy and the persistence of inflation, interest rates are likely to continue to rise to a range of 3.6%-4.1% next year.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell also noted that given the risks that the economy would continue to evolve in unexpected ways, the Fed will remain “nimble” when it comes to making any adjustments it feels necessary, both in reducing the size of its balance sheet and with regard to changes in policy interest rates.